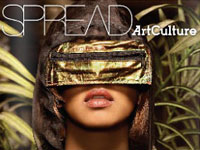

SPREAD ARTCULTURE

Jeff Bark Photographs Lucifer Falls - A Beautiful Place to Die

by: Kiša Lala

In Jeff Bark’s new series, Lucifer Falls, the water falls like a jug of milk poured over rocks, cascading down, eerily quiet in a landscape made unfamiliar – as through a gateway into a magical Shangri La – and not the parks of upstate New York, where they were actually shot.

I asked Jeff Bark why he chose to photograph waterfalls, a subject favoured by kitschy calendars and difficult to make original. Obsessing with control over his environment, Bark toiled in his studio, building sets for ‘landscapes,’ whose unsurprising outcomes led him to take the project to the road. Bark wanted to reach beyond the scope of traditional nudes and landscapes, “I wanted to take on something that was overly done. Anyone can take a picture of a waterfall – the only way I could make it different is by controlling the light.”

Light and lakes were what he grew up around in Minnesota, and so when with the help of a location scout he came to this place in Northern New York near Canada, he felt a sense of connection with the landscape. Just as he was leaving a state park he saw a tiny sign pointing to ‘Lucifer Falls,’ and the name spurred him on.

“There are a lot of colleges, its near Cornell, and tons of students commit suicide. They plunge themselves into the gorge…”

It seems a beautiful place to die. In this place, surrounded by the majesty of the falls, Jeff Bark’s photographs communicate the anguish of ending one’s life. “It also makes you feel how small you are, how fragile; nature comes back so fast…plants overtake the earth; here there is also the purity of cleansing yourself,” says Bark.

Bark would shoot when it was raining out, or about to, and when everything was saturated in the evening or first thing in the morning, 5am, when there was no light. Sometimes he triggered smoke bombs in the valley to mist the air. "You have to walk in at night, he continues, "the sun rises so fast sometimes and if the light touches the picture it becomes more like those clichéd pictures - I did take some, but I wanted to shoot a landscape with emotion," says Bark.

In one picture, I observe a girl with a stone tied around her neck, and in another, a figure suffocates under a sheet of plastic. Bark points out that under a waterfall one can't breathe very well, it's overwhelming; they are struggling on the verge, glimpsing at eternity.

Bark tells me, "I always thought photography was so easy...if someone else can take the picture than I am not trying hard enough." Brash though he might be, Bark follows through with his bite. He can bend something provocative to a work that is poignant and amusing.

He says he controls his palette by limiting it, building the set say, around the colours of a dirty baby carriage he finds, which forms his code base for the series.

That is perhaps why his photographs are governed by a dramatic sense of light, a Caravaggio light that makes the passage from dark to the pale ethereal bodies the light exposes so revelatory; he reveals veins underneath skin, "there is no light on the people, I light the air around them, but it never really touches them... The illumination of the whole picture comes from the body."

The figures appear transcendent, psychically displaced. Their faces are hidden, and they are wearing the same tunic, as though they had just left the hospital, or have found themselves awake in their nightgowns in a dreamscape.

"People have said that it was taking pictures of something they already had in their brains, like a dream, and I was showing them the picture of it..."

Bark is working on several other projects, one called "Drunk Dad," is built around tales people tell, where he gets performers or choreographers to perform, to tell a story straight, and again, after six drinks, and then, after twelve to see how things unfold. Another named "Jesus Kicks Back," started a couple of years ago is photographed around Big Sur and Carmel overlooking the cliffs and oceans and deserted freeways.

What's it about? I ask.

"If Jesus didn't want to be Jesus anymore and just wanted to surf," he says.

Jeff Bark had always wanted to be a photographer since he was twelve, "I used to write to photographers in New York and never heard back from them - now since I've been doing this - almost everyday I get a call from some kid," he says. The imperfections in his photographs speak to people.

When he did become successful as a fashion photographer, it was the lack of freedom in his professional life that led him to react against the standards of perfection imposed by the industry. When his London gallery suggested he focus on faces, he did the Flesh Rainbow series, deliberately obscuring the faces of his portraits with bags and bathroom plungers. "The reason I do this (art)," he says, "is because I don't have anybody to tell me what to do with it."

"The most beautiful you can be," Bark says, "is maybe for a week when you are seventeen. If you're touching stuff up, it kind of fucks everyone's head up. No one really looks like that. And you're constantly judging yourself against something that's not realistic.

"In my art photography I wanted to show people how they are. People seeing the Abandon series, might feel better about themselves after. You can see the beauty in a roll of skin, a patch of hair, so you don't feel as bad about yours or you can be forgiving of others. I was never interested in nude photography, to me it seems stupid..."

Flesh Rainbow is a series of funny-sad portraits with a comic-strip-like narrative. The captions diffuse the overly macabre subject and add an impish quality, "Otherwise they are quite brutal," says Bark, "like the girl with the plunger... but with a caption maybe she's Pinocchio."

Bark describes the series, Abandon, "It makes you feel a voyeur. If you're in the room by yourself you are totally relaxed, but if someone else was in the room you wouldn't do it, if your boyfriend was in the room, you wouldn't do it...it's about the most intimate time when you are alone, and it's a record of it."

A sense of quest and solitude pervades his images, from optimistic waterfalls to people alone in their rooms protecting some intimate little secret. Bark sums it up, "Everyone wants the same thing out of life I think, everyone's kind of lonely, everyone's down, seeing it in a picture, you feel you're not alone."